I bought a coffee table last week. Online, it was described as possessing a "Carrara Marble Finish with Walnut Accents." The photo showed a heavy, cold, majestic slab of stone resting on timber legs that appeared to have been hand-carved by a grandfather in Tuscany.

It arrived yesterday in a flat cardboard box that I could lift with one hand. This was the first red flag. Real marble does not weigh three kilograms. Real marble requires at least two men with back braces and a lot of swearing to move.

I opened the box. Visually, it is stunning. It has the grey veins of ancient Italian stone. It has the rich, dark grain of old wood. But then I touched it. It was warm. But, but …. Stone is not warm. Stone is indifferent. Stone should suck the heat out of your fingertips. This table was at room temperature. I tapped it with my fingernail. Instead of a solid, geological thud, it made a hollow, plastic clack.

I realised then that I had not bought furniture. I had bought a photograph of furniture glued onto a piece of compressed dust.

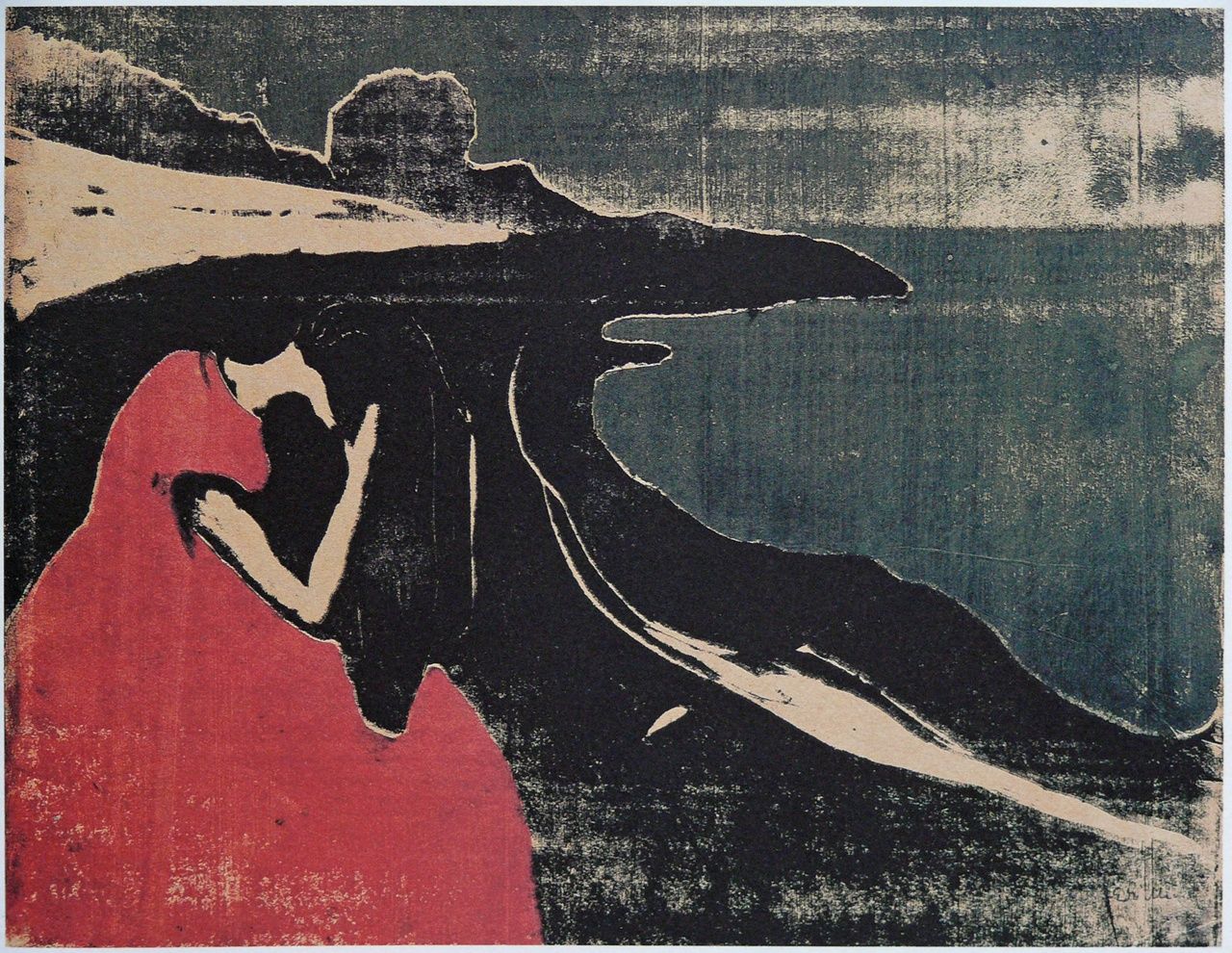

How am I supposed to spill the 19th-century tea like these ladies when my table is 100% particle board? I am now behind the society’s scandals (I’ve already missed three whispers about an exposed ankle)

Moses Wight (1827-1895) - Ladies at Tea

Sianne Ngai and the "Gimmick"

Why does this table make me feel strangely cheated, even though I always knew it wasn’t real stone? Cultural theorist and professor Sianne Ngai offers an explanation. In Theory of the Gimmick, she examines why certain mass-produced objects feel “cheap” or “gimmicky,” even when they are designed to look impressive.

Ngai describes a gimmick as an object that appears to demand excessive attention compared to the value it actually offers. It promises more than it can deliver. It also acts as a labour-saving device, but in a problematic way: it eliminates the types of labour that normally justify an object’s price or prestige.

My table fits this definition perfectly. It is trying very hard to look like a luxury object. The printed veins are exaggerated, and the surface is intensely glossy. But it bypasses all the work that real stone would require: quarrying, cutting, polishing, and transport. Instead of embodying that labour, it only imitates its appearance.

The gimmick finally knows that in capitalism, essence’s impossibility without appearance hints at something “wrong” about the essence: a system that grounds accumulation on surplus labor.

Ngai argues that gimmicks make us uneasy because they confuse our sense of cause and effect. We expect expensive-looking things to be the result of difficult or skilled work. When that relationship breaks down, the object feels dishonest.

Looking at the table, I think: You shouldn’t look this expensive when you feel this cheap. It becomes what Ngai calls an “aesthetic scam.” I am not only irritated by the table itself, but by the way it assumes I will accept its performance of luxury as real. It is a shortcut to a lifestyle I cannot actually afford.

Partner Spotlight

Check out Bilig, a modern newsletter reading and discovery platform to explore hundreds of newsletters on a wide range of topics, from media and culture to technology, books, current affairs, investing, and more!

Bilig lets you read all your newsletters in one place, with additional productivity features such as AI summaries, note-taking, and text highlighting.

The Treachery of Texture

There is a specific melancholy in touching something that refuses to be what it appears to be. It creates cognitive dissonance. My eyes tell me: "Prepare for cold, hard resistance." My hands report: "Expect lukewarm, slightly sticky plastic." This is the Ontological Betrayal of modern manufacturing.

We are surrounded by surfaces in witness protection. They are all pretending to be something else. The "wood" grain on my cabinets is a machine-printed repeating pattern. If you look closely, you can see the pixels. The "brick" wall in the café down the street is wallpaper. Somewhere, a real brick is unemployed.

We are losing our relationship with matter. We no longer interact with substances; we interact with finishes.

There is also the question of time. Real marble is geological; it measures time in eras. It enters a room like something that remembers dinosaurs and will outlive my student loans.

My table, by contrast, measures time in “lease cycles.” It is not built to endure; it is built to survive exactly one moving truck and a breakup. Sianne Ngai might say this disposability is the gimmick’s final insult: we strip-mine the earth to manufacture something with the life expectancy of a houseplant.

I wanted to be the caretaker of a rock. I wanted to own a surface. I didn’t want the laminate to peel away and reveal that my “marble” was essentially furniture-grade oatmeal. If tragedy befell my precious stone, I wanted to grieve an heirloom, staring out to sea like a sailor’s wife in the 1500s. I did not want to abandon a soggy rectangle with a sign that reads “FREE” (technically, wood) and become part of the problem.

Edvard Munch. Melancholy II (Melankoli II). 1898, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The Cat as the Anti-Gimmick

Animals are immune to the Gimmick. You cannot scam a cat with "aesthetic value." They only care about "use value."

When my cat jumped onto the new table, she expected the friction of wood or the grip of stone. Instead, she hit the "marble finish” and lost all traction. She slid across the surface like a curling stone on ice, crashing indignantly into the remote control.

She stood up, shook herself off, and looked at the table with deep suspicion. Then, she decided to test the materials. She extended her claws to scratch the "wood" leg. On real wood, claws sink in. They tear the fibres. It is a satisfying, tactile experience. On this table, her claws just skidded off the hard, laminate coating.

She looked at me, confused. She sniffed it. Since then, she refuses to sit on it. To her, this object is a glitch in the matrix. It claims to be nature, but it offers no grip.

Acceptance of the Particleboard

I looked at the table. I noticed a small chip at the corner where the delivery driver had bumped it. Underneath the majestic, grey-veined "marble," the truth was visible. It wasn't stone. The Gimmick was exposed.

Nevertheless, this table is trying its best. It is sawdust that dreamed of being a palace floor. It holds my coffee, and I can lift it with one hand to vacuum underneath it. The cat judges me. The cultural theorist judges me. But in a world that is heavy and difficult, perhaps there is something forgiving about a rock that weighs nothing.

Asena

RABBIT HOLE

Every week, I fall down a few rabbit holes. I gather here some insightful things I have read, watched, and discovered over the last seven days. If you’re looking for a bit of wonder, click 'Read More' to explore more.

I finally finished Alex Schulman’s Station Malma.

They say reading is supposed to be an escape. This wasn't an escape; it was an incarceration in someone else's misery. The book is beautifully written, yes.

And, I also like to confront the devastating cycle of generational trauma and the inherent loneliness of the human condition. (Who doesn’t?)

I have no problem with that as subject matter. However, this time it didn’t address me much.

I have written something about it and will go watch a cartoon.

I needed a hard reset. I needed a detox from manufactured feelings and perfectly timed coincidences. So, I pivoted hard. I started A Little History of the Earth by Jamie Woodward (the new 2025 edition).

I needed something solid. Something real. Something that doesn't care about my feelings. I needed science.

This book is a biography of the planet itself, taking us through 4.5 billion years of geological history. I expect the only 'generational trauma' here to be the dinosaurs, and frankly, that was an asteroid's fault, not their mother's.

Let’s see how this book turns out.

Johan Hendrik Weissenbruch. View into the basement of Weissenbruch's house in The Hague, 1888

Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum

I saw this little painting.

Honestly, this painting feels like the 1888 version of “lo-fi beats to mop to”, just replace Wi-Fi with copper pots and ambient despair. Weissenbruch looked at a dingy kitchen and decided to give it the full cinematic glow-up. The foreground is basically announcing, “I haven’t been dusted since the Renaissance”

It’s filthy, it’s dim, and it’s weirdly beautiful, the original “aesthetic interior” before Instagram learned how to romanticise mess on purpose. You can almost smell the damp stone, cold grease, and abandoned vegetables doing the absolute most. But then that light slips through the doorway, and suddenly this isn’t a basement anymore, it’s a revelation.

This is the 1880s version of a peaceful morning vlog: no espresso machine, just a barrel of mystery liquid, three battle-scarred copper pans, and some emotionally neglected cabbage leaves on the floor.

I watched The Fall by Tarsem Singh and thought I was getting a fairy tale, but it turned out to be a very pretty emotional trap.

The movie sends you across deserts and palaces with masked heroes and tragic villains, yet everything keeps looping back to one injured stuntman and the little girl stuck listening to him. It looks like imagination doing cardio around the world, even though the real story never leaves the hospital. By the time it’s over, you’re not sure if the fantasy was meant to save him, comfort her, or just make his sadness easier to look at.

That’s it. You’ve now officially reached the bottom. Thank you for reading. ❤️ Here’s your reward for your trouble: a medieval cat that will boost your positivity. (no guarantee)

If this email has been forwarded to you, blame your friend. Then join here →