. On Ownership of Digital Heritage .

The other day, I opened Instagram expecting the usual: cats with delusions, someone celebrating a special day that is no concern of mine, and perhaps some outraged people angry about someone/something.

Instead, the first thing I saw was a man playing a flute with his nose.

I watched it not because I am consciously invested in nasal musicianship, but because I couldn’t move as if the universe said, “Today you will witness this, and you will accept it.”

Okay.

When the video ended, I was left with two questions: “What just happened?” and “What exactly did I do to convince the algorithm that this is my preferred form of entertainment?”

Somewhere in the past, I must have stared at something strange for two seconds longer than polite society recommends. And the algorithm took my hesitation as a declaration of identity. “Ah,” it concluded confidently, “she enjoys unusual relationships between bodies and objects. And from now on, I am gonna feed her with such stuff.”

So, it did.

My Algorithm Thinks I’m an Aristocrat With Issues

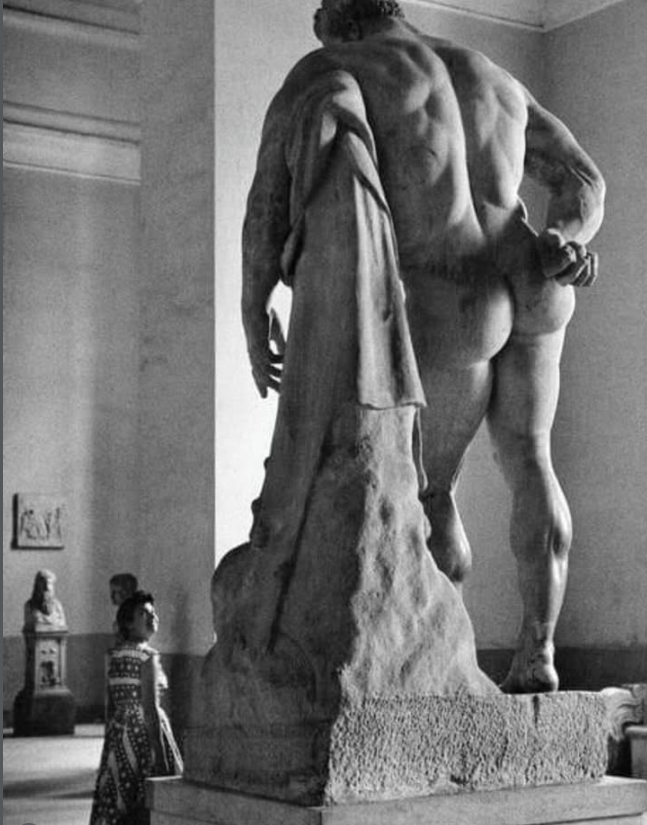

But a few swipes later, Instagram pivoted dramatically: a marble Hercules appeared on my screen, not in a museum, not in a history book, but on my phone. Unlike the nasal flutist, Hercules was symmetrical, architectural, and ethically suspicious in his anatomical accuracy.

Ancient representation of Hercules: capable of slaying monsters, incapable of processing whatever this mood is. Credit: Farnese Hercules, photo by Herbert List (1961).

For a moment, I wondered whether the algorithm had mapped my aesthetic vulnerabilities. Did it know I am easily seduced by classical sculpture? Or did it simply believe that if I enjoy nasal flute performances, I must also appreciate premium stone gluteus craftsmanship?

I began searching for Hercules with determination. Which museum housed him? Who sculpted him? How does he look when surrounded by columns and actual air instead of pixels? Eventually, I found him, and something unexpected happened: from the front, sculpted at peak physical magnificence, he looked spiritually exhausted. His posture whispered the classical mood: “I can deadlift planets, but you know what, I am emotionally unwell.”

That contrast between grandeur and collapse fascinated me. Imagine having a psychological breakdown while looking like a Renaissance fitness deity. The marble showcased the absurdity of appearing flawless while quietly dissolving inside. My burnout doesn’t look like that, and I tried to comfort Hercules in my own way, “Look, you may be emotionally collapsing but at least your marble anatomy is immaculate.”

Sadly, that materialistic pep talk didn’t help; he still looks emotionally devastated.

The Existential Folder of Marble Men

So, of course, I downloaded him. I have a weakness towards aesthetically sculpted, depressed gods or demi-gods. And then I downloaded another. And another. I now have a folder of Hercules, and I have boundary issues with him now.

Then came the existential hangover:

Are they mine now?

What happens to cultural heritage when it becomes effortlessly replicable?

If I can store an ancient monument in a folder that I own, who is the owner: me, the museum, the sculptor, or the cloud service silently billing me for storage?

Museums once controlled access through walls, guards, and velvet ropes. Now I can zoom in on a two-thousand-year-old quadriceps at 2:13 a.m., lying in bed, eating cereal. Digital heritage collapses hierarchy. The Parthenon and my cat’s ridiculous sleeping position occupy the same visual scale in my gallery. There is something hilariously democratic about that, and something unsettlingly weightless.

Heritage used to require pilgrimage: travel, patience, and standing before something larger than you. Digital heritage requires only thumb strength and Wi-Fi. You possess the image but not its aura. You collect without responsibility, curate without qualification. We have become cultural tourists without gravity or collectors without consequence.

Institutions say, “This belongs to humanity.” Governments counter, “Actually, it belongs to us.” Platforms insist, “It belongs to whoever scrolls next.” And I whisper, “It belongs in the folder in my computer.”

I Don’t Own Art, I Kidnap It Digitally

Digital heritage eliminates scarcity, creating one Hercules but countless Herculeses. However, as an object becomes more reproducible, it tends to lose its significance. A statue also serves as a potential wallpaper.

Ownership shifts from possession to interpretation. I do not own the statue; I own the act of saving it, cropping it, zooming into it, captioning it, and sending it to a friend. Somewhere in this absurdity, I realised: the moment I pressed “save image,” I became a tiny museum. A chaotic, untrained museum, yes, but a museum, nonetheless.

If everyone is a miniature curator, endlessly downloading fragments of civilisation, then heritage is no longer stored; it is scattered. It survives in the cloud, on phones, in archives, in folders. Perhaps culture is no longer preserved by institutions, but by amateurs hoarding beauty because it briefly made them feel something.

One day, long after marble erodes and museum ceilings leak, the last remaining Hercules may not stand in Rome or Athens, but inside somebody’s dusty Instagram archive. At that moment, the algorithm will whisper, “See? I knew you wanted this,” and disturbingly enough, it may have been right. The algorithm doesn’t just give us culture, it lets us stockpile it, remix it, and abandon it. We have become accidental archivists of civilisation, hoarding meaning in devices that barely have enough storage for software updates.

Whether this makes us stewards or just aesthetically motivated digital raccoons remains unclear. But somewhere between the nasal flute and the emotionally exhausted demigod, I suspect we crossed a line: heritage is no longer out there standing on pedestals and waiting to be visited. It is in here now, quietly multiplying in our pockets, waiting to be rediscovered the next time we scroll.